November is National Native American Heritage Month. It’s a perfect opportunity to learn more about Jennie Ross Cobb, a Cherokee, who also has ties to Arlington.

Jennie Ross Cobb: Cherokee, photographer, preservationist, trailblazer

Jennie Ross Cobb (1881-1959) was a Cherokee and the first known Native American woman photographer. She has ties to Arlington, living here for nearly a third of her life, and her flower shop helped beautify our town. Although better known for her time before and after residing in Arlington, we should recognize and celebrate her contributions. Jennie was a fascinating woman and a talented photographer. Prints of her photos would be a welcome addition to the Fielder Museum in Arlington.

Early life and photography

Jennie Fields Ross was born on December 26, 1881, in Tahlequah, Oklahoma (known then as the Indian Territory). She came from a large family, being the sixth of nine children. Jennie’s great-grandfather was Cherokee Chief John Ross (1790-1866), also known as Guwisguwi. He led the Cherokee Nation from 1828 until his death, including their hardships through the Trail of Tears.

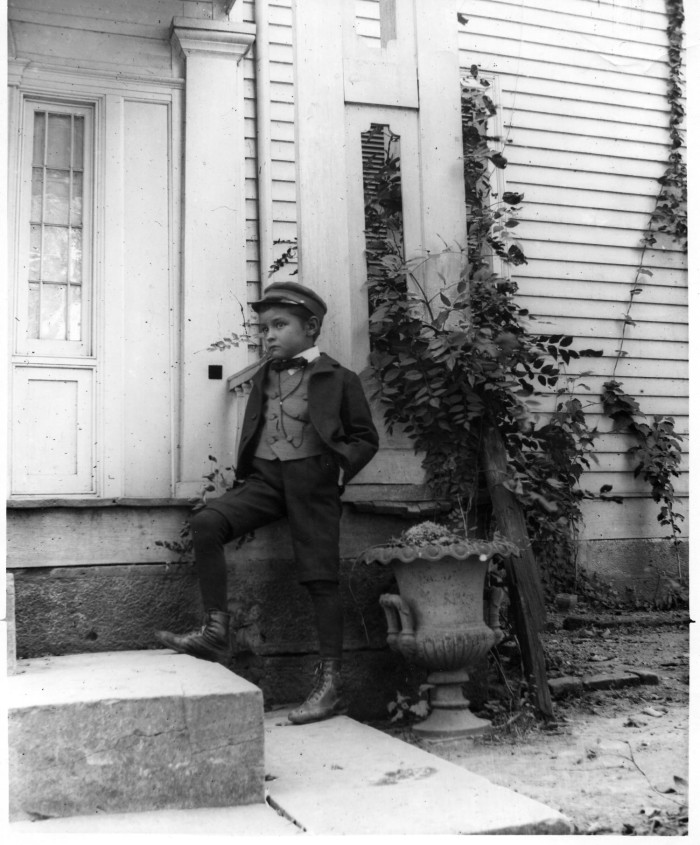

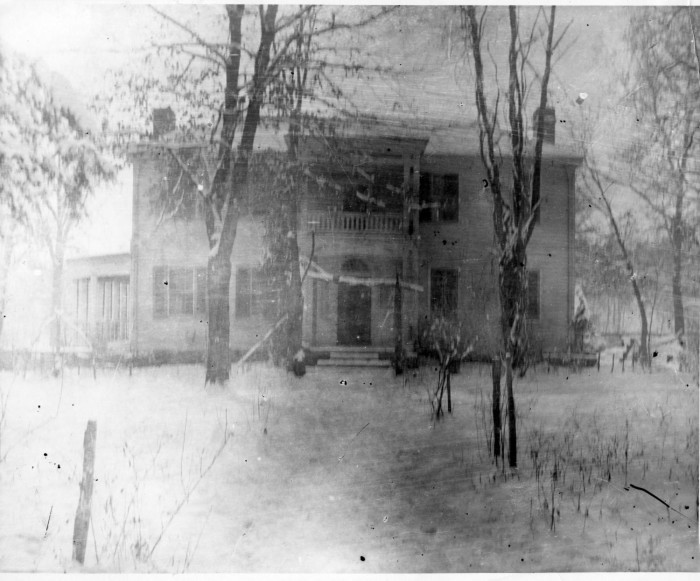

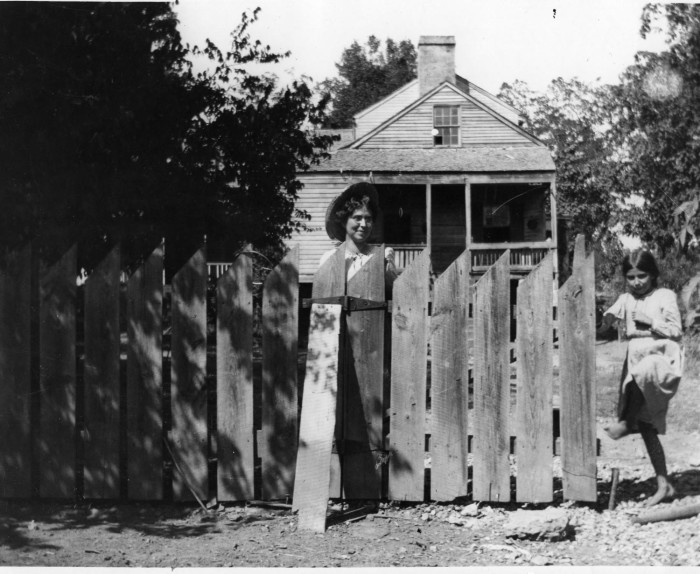

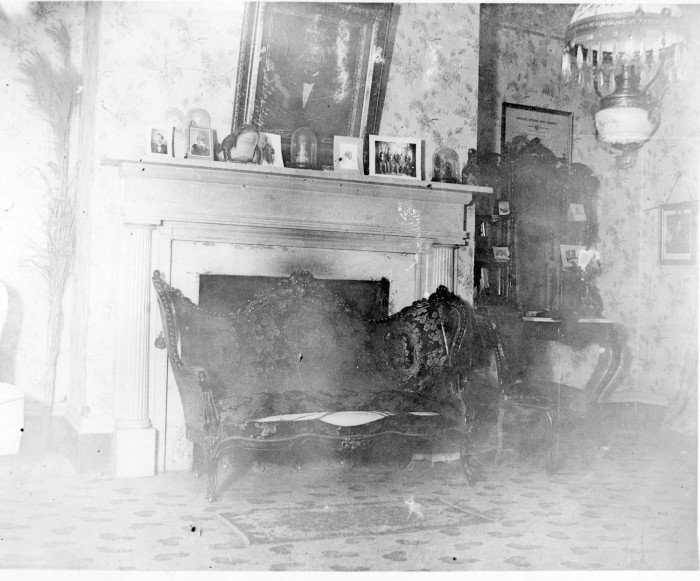

Jennie was inquisitive and pursued knowledge. As a teenager, she became interested in photography after seeing it in a newspaper or magazine ad. It’s believed she started taking photos around 1896 using a box camera. Early subjects included classmates, family, friends, and the community. She also took pictures of the George M. Murrell Home—built in 1845 and known today as Hunter’s Home—where she lived with her family in the late 1890s. (George Murrell was a wealthy merchant who married Minerva Ross, the niece of Chief John Ross.) Decades later, Jennie and her photos would guide the preservation efforts of the home.

Adult life and Arlington

After Jennie completed her education at the Cherokee Female Seminary in 1900, she became a teacher. She married Jesse Cobb (1881-1940) in 1905, a land surveyor from Dallas. They had a daughter named Jenevieve in 1906. Jennie likely set aside her photography hobby to focus on her family, who moved to Arlington in 1928.

While in Arlington, Jennie operated a flower shop for many years. Her interest in gardening and admiration for flowers prompted her to write an essay for a contest in Woman’s Home Companion, a popular magazine of the time. The Arlington Garden Club received a $1,000 prize for a rose garden in Meadowbrook Park, designed by Jennie and Jenevieve. The rose garden was meticulously cared for and was a prominent feature of the park for many years. She also made wreaths presented to winners at Arlington Downs, a local horse racing track.

Sadly, Jennie’s husband died in 1940; her daughter followed in 1945. After her daughter’s death, she raised her two grandchildren.

Museum of Native American History – YouTube

Cherokee Trailblazer: Jennie Ross Cobb (documentary)

Return to Tahlequah, death, and legacy

In 1952, Jennie left Arlington and returned to Tahlequah. Although inexperienced in museum administration, she became a curator of the Murrell Home from her youth. The State of Oklahoma had purchased the home for preservation; it opened as a museum in the early 1950s. The site is the only remaining antebellum plantation in Oklahoma.

Cobb discovered one of her old cameras and some glass plate negatives in the attic. With her photographs from 50 years earlier, she guided the home’s restoration. The photos showed how the house and grounds appeared, which provided invaluable details for restoration efforts. She also helped obtain many original artifacts and furnishings. She interviewed people and documented their memories, with her roots in the land proving to be an asset. She was the right person at the right time to make it happen and set the standard for the museum’s operation.

Jennie remained curator at the Murrell Home until her death on January 19, 1959, from a heart attack. She was 77 years old. She was buried beside her husband and daughter at Rose Hill Cemetery in Fort Worth, near Arlington. She left an influential legacy, with her photography serving as a vital link to the past and present of the Cherokee people. She was well-respected and liked by people who knew her. Jennie had a strong work ethic and took pride in her endeavors.

Further, her preservation efforts at the Murrell Home (renamed Hunter’s Home in 2018) enabled it to thrive as a local history museum. You can still visit it today. The home is a National Historic Landmark, listed on the National Register of Historic Places, and part of the Trail of Tears National Historic Trail.

Restored Hunter’s Home – Park Hill, Oklahoma

Photo Credit: Oklahoma Historical Society

Jennie Ross Cobb – Photo Collection

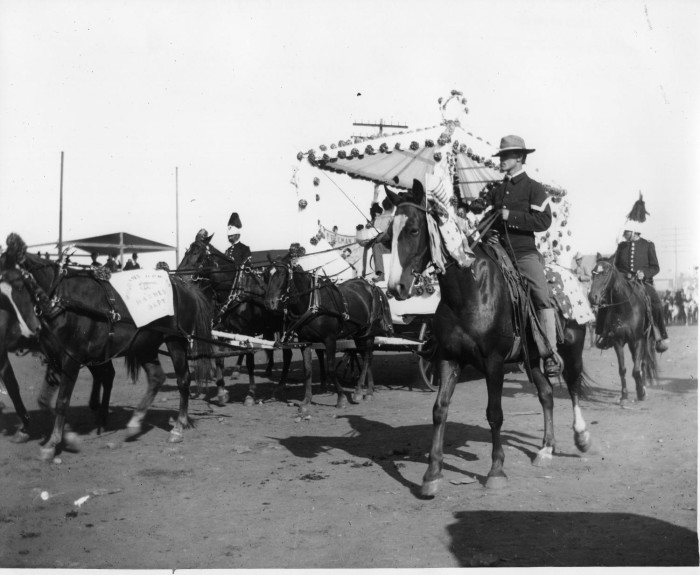

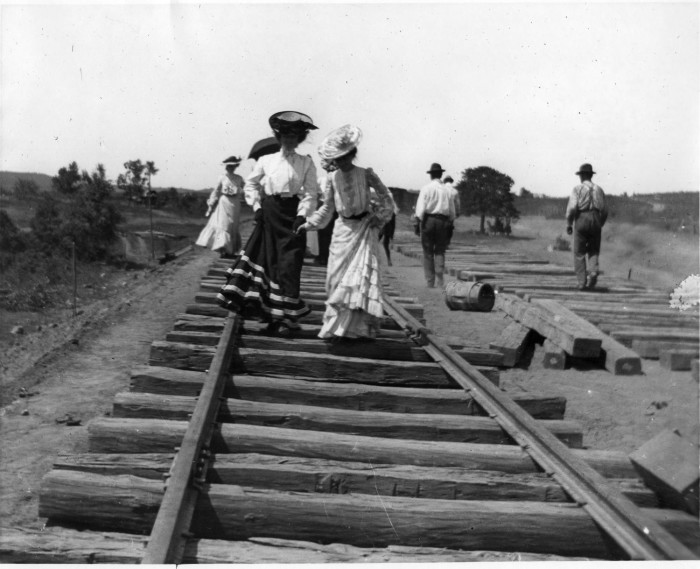

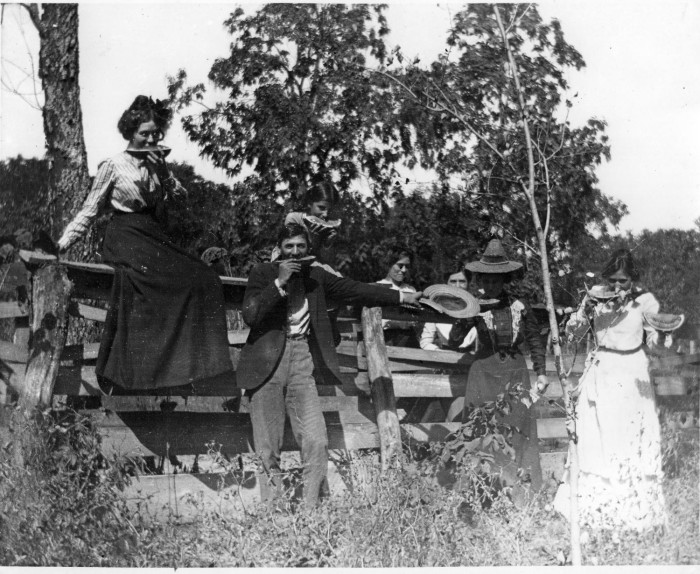

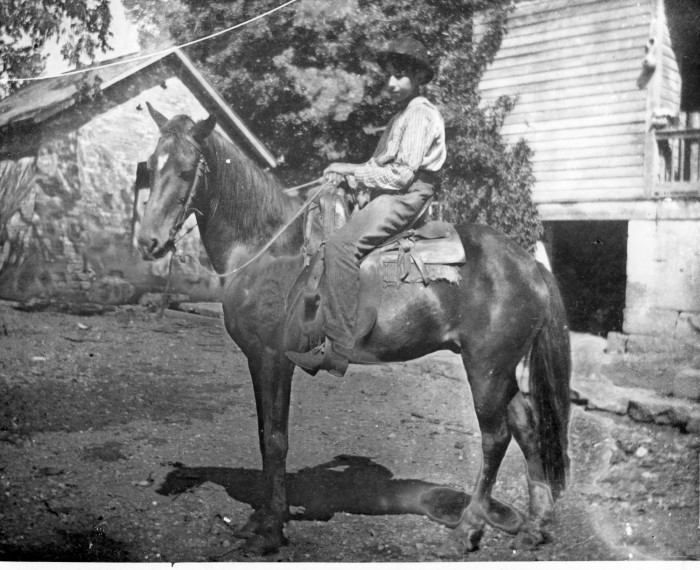

Jennie’s photographs are remarkable (and surprisingly relatable) moments caught in time. Her time as a photographer was brief, from about 1896 to 1906, and it’s believed that most of her surviving photos are from 1902 to 1905. With Oklahoma becoming a state in 1907, her photos offer a glimpse of life for the Cherokee people in the Indian Territory’s final decade. This was, of course, after the Cherokee people had been forced off their ancestral land and had to start a new life in a strange, new world. It was a pivotal time in their history.

Jennie is one of the few photographers, amateur or professional, man or woman, who captured images during this time and place. She helped document the stories of her community—although her experiences and opportunities were a more privileged slice of life than many due to her family’s reputation and status. Nonetheless, her work is seen as valuable, opening a window into a community that few outsiders had seen.

She showed promise as a photographer. There’s honesty, authenticity, and candidness in her photos, and they’re quite original. They show people and places from her community with intimacy and interest; they’re also detailed, distinctive, bold, and beautiful. She had an eye for composition and storytelling.

Photo Collection

Included here are the surviving photos of the Jennie Ross Cobb photo collection, as maintained by the Oklahoma Historical Society.

Photo Credits: Jennie Ross Cobb and the Oklahoma Historical Society.

For optimal viewing, consider viewing these photos on a tablet or laptop.

Karen Shade, who researched Cobb’s work for a 2020 exhibit, said: “Jennie, to me, is fascinating as an individual who was able to capture people unguarded and even a little charmed by the camera. So much photography from that era is stiff, formal and posed, but in her known works, you see personalities. It’s a step ahead of where photography would go in the decades following. Her unassuming and easy manner must have put people at ease, allowing her to get the kind of shots she has left for us.” [Quote from High Country News]

Ms. Shade also added: “She may be considered an amateur photographer, but that shouldn’t imply a lack of skill or quality. We see in the nearly two dozen images definitively attributed to her [that] Jennie had the eye of a true artist. The perspective, framing, and lighting in several images demonstrate a real talent.” [Quote from High Country News]

The Oklahoma Historical Society maintains her surviving photography collection of twenty-one photos. The photos have toured and featured in exhibits. One of the more notable exhibits was “Through the Lens: The Photographic Legacy of Jennie Ross Cobb,” displayed at the Cherokee National History Museum in 2020-2021. Even so, relatively few have seen or studied the photos—a wrong that we must work to right, as they tell an important and undertold story.

Resources

- Oklahoma Historical Society – photo collection

- Wikipedia – Jennie Ross Cobb

- American Indian Magazine – Lasting Impressions: Jennie Ross Cobb, First Female American Indian Photographer, Framed Cherokee Life in Indian Territory

- Find-a-Grave – Jennie Fields Ross Cobb

- High Country News – Images from the first-known Native American female photographer

- PBS – The life and legacy of Native photographer Jennie Ross Cobb (short video clip)

- YouTube – Cherokee Trailblazer: Jennie Ross Cobb (23-minute documentary)

- Museum of Native American History.org – Historic Trailblazers: Jennie Ross Cobb

- Visit Cherokee Nation – Through the Lens

- OK History.org – Family of Jennie Ross Cobb Donates Photographic Glass Plates to OHS’s Hunter’s Home (Press Release)

- Hunter’s Home – Oklahoma Historical Society

Blog post by Jason S. Sullivan, 11-27-24